|

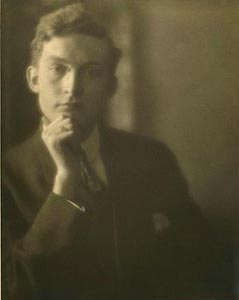

Clarence H. White (1871 -1925) became one of the most influential photography teachers of the 20th century: Margaret Bourke-White, Paul Outerbridge Jr., Dorothea Lange, and Karl Struss were among his students. When the Clarence H. White School of Photography opened in New York in 1914, White had already been a photographer for two decades. His work burst upon the national scene in the late 1890s, in the first wave of modernist art photography.

|

|

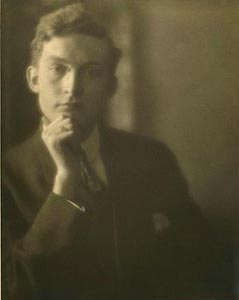

- Eduard J. Steichen

- Portrait of Clarence H. White (1905)

|

|

By 1900 the influential critic Sadakichi Hartmann would write, “Clarence H. White of Newark, Ohio sprang into being as an artist with the rapidity of a meteor rushing through space.” Indeed, the world beat a path to the small town of Newark — while still in his twenties, White organized exhibitions that attracted participation from the leading lights of the new artistic photography movement. Works by Alfred Stieglitz, Gertrude Kasebier, Eduard Steichen, Frank Eugene and Robert Demachy decorated the walls of the Newark YMCA in 1899.

Sadakichi Hartmann was among the first to identify White’s particular talent at elevating homespun scenes into photographic art. Noting that a person in Newark, Ohio would likely be limited to the art education that could be obtained from illustrations in magazines, Hartmann wrote: “A man in such a position has to rely largely upon himself and the observation of that which surrounds him in daily life. He will trust to the report of his own eyes and pick out from his surroundings that which seems to him practical and worthy of artistic treatment. This is exactly what Mr. White has done… Those old-fashioned interiors taken against the light of big windows, those old staircases, doors and porches, the quaintly patterned gowns of the women who people these scenes, all tell their story. There is something so idyllic in his pictures, something so simple and subtle… it is a poetry which comes naturally.”

|

|

|

The eminent photographic historian Peter C. Bunnell also cites popular magazine illustrations as an important influence on White’s photographic works:

What is especially fascinating, however, is what occurs when White is commissioned, as he was in 1901, to take up literary illustration himself. Through the assistance of Stieglitz, White received the commission to illustrate a new edition of the novel Eben Holden by Irving Bacheller. From this commission he received another, in 1903, to illustrate a narrative for McClure’s Magazine: “Beneath the Wrinkle” by Clara Morris. The photographs used in these publications have interest in comparison to his others. One can sense in them a relative incompleteness in their depiction; a stronger sense of the dramatic moment as the scene has been excerpted from the continuity of the verbal narration, a sort of narrative dissolution. In the context of the publication the pictures are successful and, like motion picture stills today, they struggle in any attempt at summation. When comparing them to his other pictures, which had struck some critics with their sense of narration, one recognizes how these writers intuitively understood that White was not illustrating, but summarizing experience.

Inside the Photograph (Aperture, 2006) pp. 47-48 (Aperture, 2006) pp. 47-48

|

|

|

|

These two portraits by the leading New York theatrical photographer Napoleon Sarony depict Clara Morris at the height of her popularity as an actress.

|

|

Like White, author Clara Morris began her professional career in Ohio; she was 21 when she made her debut as an actress at Woods Theater in Cleveland in 1861. She quickly moved on to New York where she was an immediate hit. Known as the leading “emotional actress” of her day, Miss Morris prepared for her roles by studying real life, going so far as to visit an insane asylum before playing a mad scene.

Upon seeing Clara Morris in Camille, the great Sarah Bernhardt said “Mon Dieu! This woman is not acting; she is suffering!”

Miss Morris largely retired from the stage in 1890 and devoted herself to writing, producing an autobiography, a daily newspaper column for 10 years, and numerous magazine articles. She died in 1925.

|

|

|

|

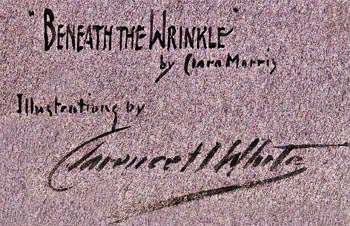

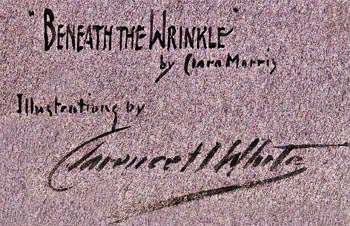

When White submitted his illustrations to McClure’s, he presented the photographs on individual mounts with decorative ink borders and titles. The first image in the series was intended as a title page design and has bold lettering in White’s hand. The whole ensemble, seven signed prints of six images, was presented in a purple paper portfolio (inscription, left.)

The portfolio and its contents were rediscovered in the late 1970s, when a Long Island home was being cleaned out after the death of its owner, a retired editor of McClure’s.

|

|

|

Alfred Stieglitz, founder of the Photo-Secession and leading exponent of pictorialist photography, re-published three of White’s photo-illustrations in 1903 and 1905 (two from Eben Holden and one from “Beneath the Wrinkle”) in his influential art photography journal Camera Work. One image from “Beneath the Wrinkle” was part of Stieglitz’s personal collection of photographs, and exhibited internationally.

|

|

Even though most magazines were illustrated by reproductions of paintings or drawings in the early years of the 20th century, the use of photography as a medium of illustration was already well-established. As early as the 1840s, the Scottish calotypists Hill & Adamson made photographs based on the works of Sir Walter Scott, and in the 1870s, Julia Margaret Cameron produced two volumes of photographic illustrations to Tennyson’s Idylls of the King. By 1900, travelogues and other popular lectures were presented all over the United States, accompanied by photographs projected onto a screen by “magic lanterns.” Most of the photographs used in these lectures were documentary in nature. However, posed and costumed scenes were sometimes produced to accompany popular songs or stories. As is usually the case with illustrations, these images depict only a portion of a narrative; when removed from their context they take on a cryptic quality. White’s photographic illustrations share this characteristic but have additional artistic intent: the photographer made use of his considerable range of aesthetic techniques and exhibited his illustrations alongside his other early modernist images as independent creative works.

|

|

|

- F. Holland Day: Portrait of Sadakichi Hartmann (circa 1906)

|

|

Sadakichi Hartmann singled out White’s illustrations in his review of the 1904 Photo-Secession Exhibition at the Carnegie Art Galleries in Pittsburgh, a display he considered “indisputably the most important and complete pictorial photographic exhibition ever held in this country… so far superior to anything of its kind I have ever seen before, that I consider it a privilege to have viewed it and to have found real pleasure in my task of studying it.” Reviewing White’s images in the exhibition, Hartmann had praise for their “power of characterization”–

Clarence H. White, a sincere, straightforward talent of rare refinement and never-tiring student in quest of beauty, has convinced me more than ever that his is a rather limited field, but that he stands absolutely unique as a photographic illustrator. His illustrations for Eben Holden and “Beneath the Wrinkle” will not be easily surpassed…

|

|

|

Despite such glowing words, and despite White’s belief that photography was a medium well-suited to serious, high-class book and magazine illustration, his works only illustrate two additional publications: Songs of All Seasons, a book of poems by White’s uncle Ira Billman (1904) and Gouverneur Morris’s article “Newport the Maligned” in Everybody’s Magazine (September 1908.)

When “Beneath the Wrinkle” was published in the February 1904 issue of McClure’s, only three of White’s six illustrations appeared in the pages of the magazine. Now, more than a century later, the American Museum of Photography presents all of the images together with the text of the story for the first time… on the next page of this exhibition. |

|

|

(Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978)