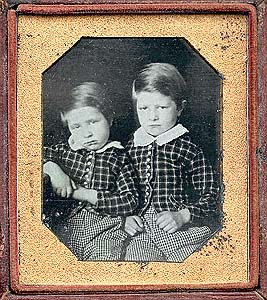

Photography was born pure. In the beginning, there was the daguerreotype. Each daguerreotype was made individually in the camera. No negative was used. Since photography was so new, and seemed so miraculous, daguerreotypes were prized for their perfect accuracy in recording a scene or making a portrait. Dr. Oliver Wendell Holmes called photography “the mirror with a memory.” Why would anyone try to improve upon such perfection?

|

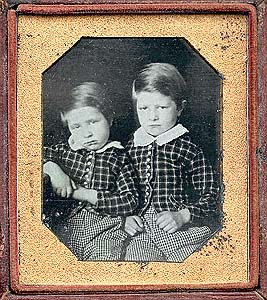

Unidentified photographer, Two Boys in Matching Outfits. Daguerreotype, circa 1845 >

|

|

|

|

|

Perfection? Well, almost. Mirrors reflect images in full color; daguerreotypes do not. Even the earliest and most enthusiastic news reports about the daguerreotype process often mention the absence of colors — an important piece of information for those reporters struggling to describe the first photographs to thousands of readers who had never seen even a single camera-made image. Within a matter of months the first photographic studios opened, enabling people to see (and own) the miracle for themselves… and to notice that something was missing…

|

It didn’t take long before someone had the bright idea of adding a little color by hand to “improve” daguerreotypes. In fact, six of the first eight photographic patents in the United States covered new methods of coloring daguerreotypes. Soon, nearly everyone was depicted with rosy pink cheeks and glittering gold rings — and occasionally, daguerreotypes were as colorful as miniature portraits painted on ivory.

|

Unidentified photographer: Boy and Girl in Blue Tunics. Hand-tinted Daguerreotype, circa 1850 >

|

|

|

|

|

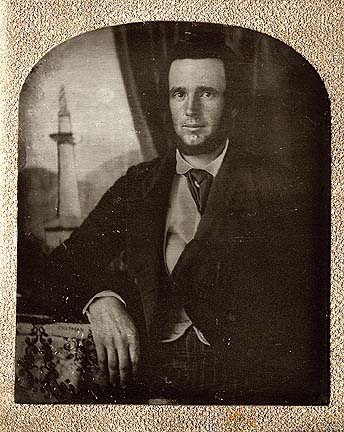

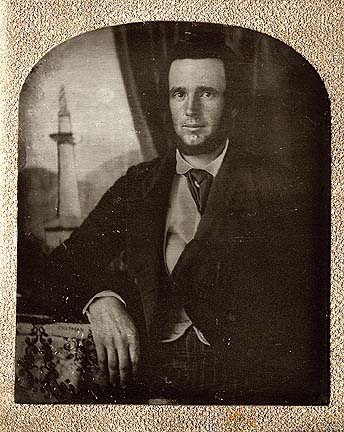

Another early “improvement” in daguerreotype portraiture was the use of painted backdrops. The first photographic studios opened their doors in 1840, and backdrops were introduced within a year or so. Based on conventions found in portrait paintings of the time, daguerreotype backdrops could make it appear as if the subject was seated beneath trees along a quiet riverbank or posed beside a window showing a seascape or a local landmark.

|

< Chapman, Portrait of a Man with Backdrop of Washington Monument, Baltimore. Daguerreotype circa 1844

|

|

|

|

Somewhere along the way, a line was crossed: the purity and perfect accuracy of photography took a back seat to the embellishments that could soften the harsh edge of reality. Some of the greatest daguerreotypists ( notably Southworth & Hawes of Boston and Jeremiah Gurney of New York) often produced superb character studies with nothing more than the basics — sensitive control of lighting, pose, and composition. But even these early photographic masters were sometimes required to bow to the public taste for elaborate hand-coloring or romantic painted backgrounds.

|

|

More extensive manipulation of the daguerreotype image required ingenuity. John Adams Whipple of Boston patented a vignetting method to produce what he called “Crayon Portraits.” Whipple’s method used white paper on a wire frame, placed between the sitter and the camera. The white paper was moved during the exposure, creating a blur that blends seamlessly with the backdrop. The result: the subject’s head stands out from the plate, while the shoulders “dissolve” softly into a celestial white cloud.

|

Unidentified photographer: Vignetted portrait of a woman resting her head on her hand. Daguerreotype, circa 1853 >

|

|

|

|

|

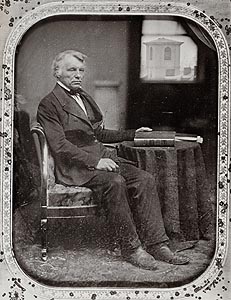

A more elaborate method of manipulating the daguerreotype portrait was employed by the Southworth & Hawes studio. This remarkable image shows a man beside a window overlooking the steeple of the Brattle Street Church. Because of the lenses used during this early period of photography, the sitter and the steeple could not have been portrayed together in a single exposure; one or the other would have been blurry and out-of-focus. So Southworth & Hawes must have masked off part of the plate when the portrait was made, then taken a second exposure showing only the window.

|

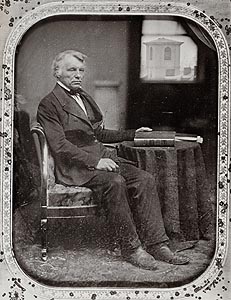

< Southworth & Hawes, Man Seated Beside a Window Showing Brattle Street Church. Daguerreotype circa 1850. Matthew R. Isenburg Collection

|

|

|

|

Now, another line was ready to be crossed: the line between what’s real and what’s fabricated. The view of the Brattle Street Church was real — it’s what you would have seen when you looked out a window of the Southworth & Hawes studio in Boston. But suppose you made the first exposure of the man in the chair, and then took the plate to Washington D.C., where you filled in the blank part of the image with a picture of the U.S. Capitol. The result would be a portrait showing the sitter was photographed in Washington when in reality he never left Boston!

|

|

As early as 1858, the photography manual The American Handbook of the Daguerreotype provided instructions for using masking and double exposures to make one person appear twice in a single photograph. Within a few years, studios in the U.S. and other nations were offering multiple exposure portraits –human clones, created with a camera. And that’s only one example of the often ingenious, sometimes insidious uses of early manipulated photography— from humor to political propaganda to communicating with the dead.

For more, click a link below.

|

J.C. Higgins & Son (Bath, Maine): Triple Exposure with Barrel. Albumen cabinet card, circa 1890.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| –Click for Next Exhibit– |

–Click for Photographic Fictions Menu– |

–Click for Museum Home Page– |

|